A Look at “Apropiacionismo Cultural” in Santiago, Chile

¡Mari mari kom pu che! Hello, everyone! The greeting, or chaliwün, I used in this blog post is in Mapudungun, the language of the Mapuche peoples in Chile. I am currently taking a class in Mapuche Culture and Language and am using any chance I can get to practice the newly learned vocabulary. I took this class because it’s important to remember that before Spanish was forcibly introduced in Latin America, there were a plethora of Indigenous languages spoken, some of which continue to exist today. However, due to the violent process of colonization, it can be easy to forget this history. Nonetheless, I believe that by learning Indigenous/non-Eurocentric languages and cosmovision, we can start to decolonize our mentality of the spaces we inhabit at the individual level, as well as actively recalling the histories of the places we inhabit.

A month has already passed by since I first arrived in Santiago, and I cannot believe I’m about to approach April. So far, my transition to living in Chile has been such a special, intimate process for me. I can already see myself starting to become a more assured and self-confident person because when you are in a foreign country, one must learn all over again how to relate to their surroundings and communities for the best experience possible. One super necessary lesson that I’ve learned so far is that no one, whether it be your host family or local store clerk, can ever read your mind so it is very important to speak up and vocalize your needs, concerns, or questions. There will be some aspects of your host country that you may never like nor tolerate, and while your first inclination may be to embrace everything in the name of “cultural immersion”—which was, I admit, certainly my first instinct—one must remember that acknowledging the unpleasant parts is also totally fine. Having that honesty only makes for an enriching study abroad experience.

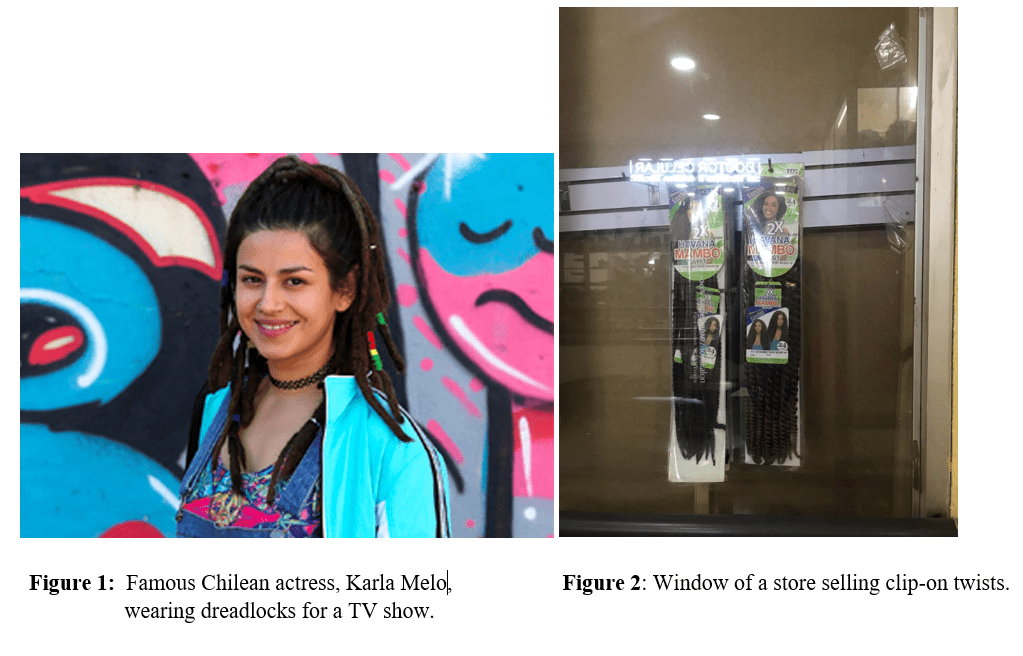

One of the unpleasant things that I’ve encountered in my host country has been the seemingly widespread cultural appropriation of Black hairstyles. I didn’t realize how common the usage of dreadlocks, twists, or braids (such as cornrows) existed in Chile until I walked along the streets of Santiago. I spotted young and older women and femmes, such as high-school students, wearing them on the metro on my way to class. I saw white men, and even women, wearing dreadlocks wrapped in a turban. I couldn’t even escape seeing these acts of appropriation when I watched Chilean TV shows on Netflix. However, the part that disturbed me the most was that many Chileans did not realize the harm nor consequences of their actions. I should have known that anti-Blackness is a global phenomenon.

When I told my host mom about how uncomfortable I felt seeing many Chileans wearing these hairstyles, she told me that many Chileans wore dreads or braids because it was trendy: “We, Chileans, are copycats. We imitate everything from the West”, she said. For my host mom, the act wasn’t so much of cultural appropriation, but rather another trend exported from the West. She told me not to get too frustrated because the Chileans who wore Black hairstyles did not have malicious intentions. As a matter of fact, when my host mom’s daughter (who is 50 years old) came over for once (a very light dinner that Chileans eat in the evening), she casually talked about wanting to get braids but deciding against it because of how time-consuming it would be to maintain them.

Unsatisfied with my host mom’s response, I chose to ask one of the Middlebury staff members, Paulina, about her view on this issue. Paulina repeated something similar to what my host mom shared but added that many who appropriated Black hairstyles did so to show support for the consumption of cannabis, which is currently illegal—despite being widely consumed—in Chile. I still felt troubled by both responses because no matter the intent, Chileans were still appropriating Black culture and reducing it to a stereotype (for instance, that all Black people smoke weed or do drugs).

I thought about this phenomenon in the socio-political context that Chile has found itself in over the past few years. My host mom and the Middlebury Chilean staff mentioned that before, Chile used to be composed of mainly white people and Indigenous people. However, given the influx of Venezuelan, Peruvian, Bolivian, Colombian, and Haitian immigrants over the past decade, the face of Chile has been changing a lot, with about 7.5% of the population composed of immigrants (according to a 2020 statistic). For example, it is very common to see Haitian and Venezuelan immigrants (at least those from a low-income background) working low-wage jobs as delivery drivers or Uber drivers. Some immigrants, depending on how favorable Chilean immigration policies were at the time of entry, have managed to open restaurants and other businesses. Nonetheless, for the most part, many have been cast as second-class citizens compared to other Chileans, with policies systematically denying refugee status and/or making it hard for migrants to live in Chile. And like many other migrant-receiving nations, Chile has not escaped embedding xenophobia and racism in their policies, insinuating that migrants transport drugs, crimes, and even diseases like Covid-19, as stated in former President Sebastian Piñera’s April 2020 press release when he emphasized the importance of securing the border. In a country where right-wing companies dominate the media, these remarks and xenophobic sentiments evidently cause Chileans to view migrants not as refugees, but as people who “ruin the country” by transporting drugs and crimes.

For Black migrants, this unwelcoming environment is worsened by racism as well, especially in a country where there exists a lack of racial consciousness by many white Chileans. One can easily turn to the Ukraine-Russia crisis as an example of the double standard that exists for non-white migrants. Where Ukrainians, due to their whiteness and middle-class status, have the privilege to be recognized as refugees worth of foreign aid and welcome, many Afghani, Yemen, Syrian, Haitian, and other BIPOC migrants have been met with dehumanizing policies, their crisis largely ignored by the public eye. Not too long ago, for example, the very United States that offered $13.6 billion worth in aid to Ukraine and had Biden flown to hug Ukrainian babies at the Ukraine-Poland border, was the same country that did not hesitate to whip Haitians at the border and cage migrant children, even though they too were fleeing violence and instability.

Locally, in Chile, we can notice this “otherness” out in the public, besides the appropriation of Black hairstyles. In my Migration, Antiracism, and Decolonization class, my professor talked about the inherent nationalism present in many Chilean feminist movements, a topic of great debate amongst feminist circles in Chile. One rarely sees a “Haitian Migrant Lives Matter ” or a “La vida de las migrantes Venezolanas importan” (Venezuelan migrant womxn matter) sign at these marches, my professor pointed out. She was right.

Earlier in March, during the Huelga Feminista on March 8th, amongst the sea of heads that surrounded Plaza Italia, I tried to see if I could find any activists of color who would bring attention to the various struggles many migrant women of color face. While I didn’t see any activists of color nor demands that supported womxn migrants, I did see a lot of migrants of color (particularly Haitian women) selling food and beverages to the attendees. I also saw many non-Black Chileans wearing dreads or braids while performing or chanting. Part of me wondered how Black womxm migrants reacted at the appearance of their hairstyles on non-Black people, especially when hair represents a unique/specific embodied experience. Although everyone chanted “Nos atacan y nos violan y nadie hace ‘na” (“They attack us and rape us, and no one does anything”), I knew that the Chileans who consumed Black culture had the privilege of escaping the tangible violence of racism and discrimination tied to Blackness and migranthood. This situation brought a lot of questions to my mind, namely about the privileges of protesting. Who gets to argue and show up to protest in the street? Who is defending the rights of immigrants? Whose violence is ignored due to being undocumented, non-white, and unable to speak the host country’s language well?

In retrospect, the lack of participation of migrants of color in these marches reflected more profoundly the way that white feminism in Chile still excludes many. My professor and I discussed this fact, both agreeing that the feminist movements in Chile still have far to go before they’re truly intersectional. However, while I firmly believe that cultural appropriation will always be insensitive and unjustifiable, my professor thinks that this apropiacionismo cultural, can become less extractive if the person/appropriator actively participates in the struggle for justice alongside Black and Brown folk. I disagree with her on this point but am somewhat optimistic that as these movements become more intersectional, there might be more space for dialogue and a racial reckoning for many Chileans. I am also aware that social movements don’t occur in a vacuum, and that the actions of the United States regarding racism, or any other issue, fundamentally shape the demands of protests in other parts of the world. Nonetheless, I hope to continue talking to my Chilean peers, professors, community, and even immigrants of color, about this topic during the rest of my time in Chile. More importantly, I hope to continue looking at Chilean social movements with a critical eye.

¡Pewkayael! ¡Hasta luego!