Photo Essay: “La calle habla lo que la prensa calla”

Hi everyone,

I hope that everyone is enjoying their summer. It has been a very long minute since I’ve uploaded a blog post; however, I’ve experienced many, not-so-great things in Chile this past month which have forced me to pause my study abroad experience, take care of my mental health and adapt once again to Chile. (I may dedicate my final post to reflect more in depth about the lessons I’ve faced from my tribulations). However, despite all the (unnecessary) stress I’ve faced, there have been pockets of joy that have made my problems more bearable. I am incredibly grateful for the community of friends, volunteers, Chilean students, program staff and strangers that I have formed here in Santiago. If I learned anything from this past month is that it is possible to transform a foreign place into a home when one has formed a community. By stepping outside of my own comfort zone, meeting new people and being vulnerable enough to share my own problems to others in a foreign country, I have been able to find people who have shown me great empathy and solidarity.

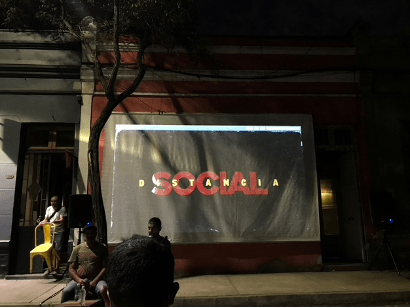

In a society that keeps us segregated and profits from our separation, forming community with others different from oneself is probably one of the simplest, yet radical political acts one can do. I took away this lesson not only from my past experiences, but also from a Chilean documentary I had watched a while ago in March. One weekend, my friends and I were walking around Barrio Yungay, a rich, cultural neighborhood declared as “patrimonio cultural” (cultural heritage) by the city and bumped into an outdoor screening of a documentary called Distancia Social, or “Social Distance”.

We sat down for 2 hours, surrounded by an audience full of residents of the neighborhood, to watch as the director recorded himself spending a month living in a poor neighborhood in Santiago off the “ingreso familiar de emergencia” (emergency family income) and “caja de alimentos” (box of food) distributed by the government at the start of the pandemic. Throughout the documentary, we witnessed as the director, Fernando Lasalvia, prepared simple meals in his cramped room located in Villa Portales, interviewed passerby Santiaguinos, and related back the activity he saw in the streets during the few times he left his apartment: people heading to work despite lockdown restrictions, rich comunas empty of people who could evidently afford to stay in quarantine, police abuse, communities performing mutual aid in the form of “ollas communes” (communal kitchens), and demonstrations. Lasalvia’s intentions were to expose the “other” Chile that the media/news failed to talk about. While Piñera’s government portrayed themselves to be handling the pandemic very well and rigorously protecting the public, Lasalvia saw a different story unfold while out in the streets. He met Chileans that could not afford to stay quarantined, who had waited weeks to receive any sort of monetary aid from the government, transit workers who felt their labor and safety were being neglected, people who attended ferias or participated in ollas communes because the government’s caja alimenticia lacked substantial nutrients or because they never received one in the first place, and saw cash-stripped people who waited in long lines in front of banks to withdraw from their savings accounts. In the end, not only did Distancia Social function as proof of the blatant neglect and mishandling of the pandemic by the Chilean government, but it also demonstrated the unequal, disparate realities between what millions of ordinary Chileans lived, and what the elite (media, corporations, and the government) claimed reality to be like. As I mentioned in my last blog post, the right wing dominates mostly all the media outlets in Chile, and some of these very elite own supermarkets, chain restaurants, banks etc. In a country where this huge power of communication lies in the hands of a few businessmen, education is privatized, and inequality is profound, it is very easy to see how millions of people can be kept ignorant.

At the end of the screening, Lasalvia, who had been in the audience, wrapped up the event by imploring the crowd to never forget the reasons that drew them to protest outside in the streets back in 2019. He said that while there may not be presently protests occurring at the same large scale as they did during the estallido social, everyone must still keep their guard up. With the development and election of the new Constitution underway, many news channels have given the new Constitution and the constitutional convention itself mostly negative press, fueling distrust amongst Chilean voters, some who already are victims of misinformation campaigns seeking that the public reject the new Constitution. The director cautioned the crowd of these challenges and urged them to stay vigilant so that a new Chile can soon be born.

In a snapshot of the film, Lasalvia captures a graffiti in the awning of a store that read, “La calle habla lo que la prensa calla”, which translates to, “The streets say what the media silences”.

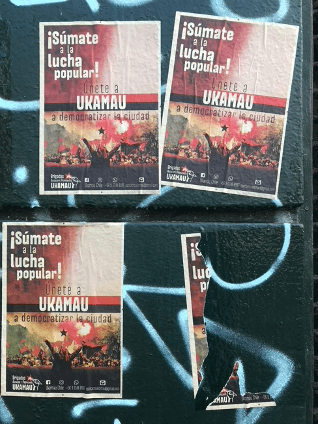

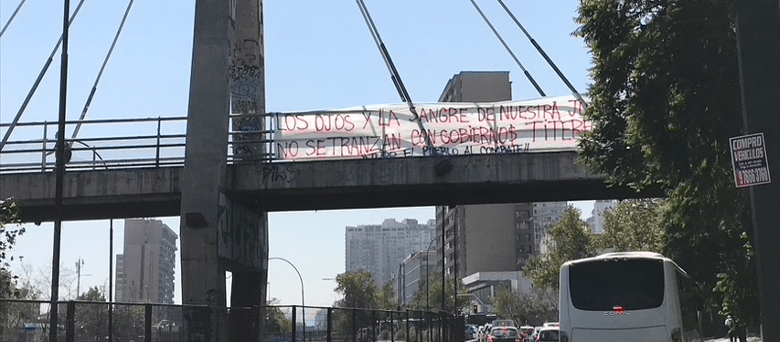

Inspired by this quote, I chose an array of photos taken in the streets that forces passerby people, both Chileans and foreigners alike, to pay attention and remember that the fight against inequality persists.

Barrio Brasil, Santiago

Av. Manuel Rodriguez Norte, Santiago

Cementerio General, Santiago